Listen to the article

Ireland’s rapidly expanding data centre sector, driven by the AI revolution, is raising critical concerns over energy consumption and climate commitments amid mounting investment from global tech giants.

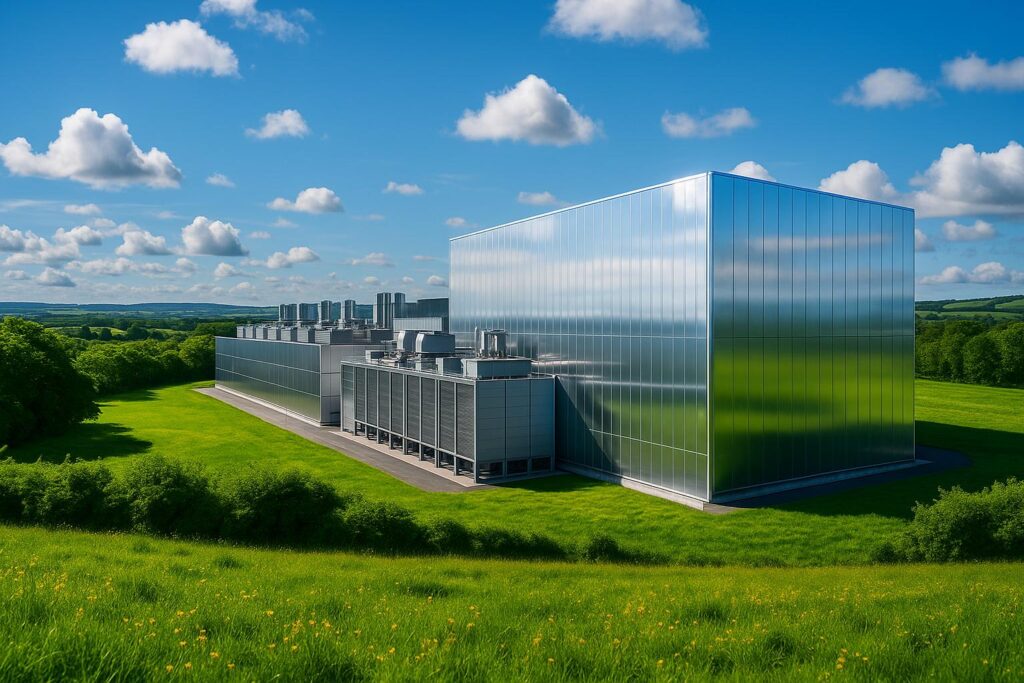

Strange though it may seem, the best vantage on the unfolding global rush into artificial intelligence in Ireland remains a walking trail on the Dublin mountains, where the hulking shapes of data centres below now offer a visible reminder that the AI revolution, for this island, is as much about concrete and cooling systems as it is about algorithms. [1]

Official statistics underscore that visibility. According to the Central Statistics Office, data centres consumed more than 22% of the Republic’s electricity in 2024, up from about 5% in 2015 and continuing a rapid upward trajectory that saw consumption rise by roughly 10% between 2023 and 2024. That shift has transformed a once-modest sector into one of the largest single drains on national power. [1][2][3]

Those numbers help explain why many of the biggest global technology and investment firms are aggressively expanding their footprint here. Recent dealmaking reported in business pages , from Google-owner Alphabet’s purchase of Intersect to Meta’s acquisition of Manus, Nvidia’s investment in Intel and Amazon Web Services securing planning permission for new Dublin sites , illustrates how multinational capital and corporate strategies are reshaping Ireland’s industrial map. The prospect of Kingspan spinning off a data-centre outfitter further highlights how domestic firms are seeking to monetise the boom. [1]

That expansion is colliding with hard engineering and public-finance realities. AI workloads are power-hungry and require new grid connections, battery storage and offshore wind developments; much of the infrastructure to supply that power will need to be paid for or underpinned by public investment. Industry advisers and regulators have flagged the need to manage grid stability and connection rules as these projects scale. [1][4]

Regulatory shifts have followed. The Commission for Regulation of Utilities issued new rules for how data centres connect to the grid, a move welcomed by industry bodies representing wind and energy developers and by groups backing cloud infrastructure, while environmental campaigners warned that a “colossal” appetite for electricity risks diverting renewable output and increasing reliance on fossil-generated power. Those divergent responses show the policy tension between attracting foreign direct investment and meeting climate and energy targets. [1][4]

The broader energy context compounds the challenge. International analyses warn that AI will multiply data-centre electricity demand globally: the International Energy Agency projects data-centre consumption could roughly double by 2030 as AI-driven workloads proliferate, and the European Central Bank has cautioned that energy use by data centres could rise sharply over a short period. Industry forecasts similarly argue that AI will drive demand for denser, more sophisticated facilities and cooling systems, making infrastructure upgrades and long-term planning an urgent priority. [5][6][7]

That urgency is sharpened by distributional concerns at home. While a handful of US and other multinational firms now account for a significant share of corporation tax receipts and large-scale investment, the economy outside that cluster remains dominated by Irish-owned small and medium-sized enterprises that supply most jobs. Business leaders, community groups and campaigners alike question who will ultimately benefit from the public expenditure on cables, ports and wind leases that support offshore renewables and the new grid capacity. [1][2]

Views from the Dublin mountains are therefore likely to show more data-centre roofs in the years ahead, but they also capture a broader contest over energy, planning and the allocation of public resources. How regulators, government agencies and communities reconcile the twin aims of supporting high-value inward investment and meeting decarbonisation commitments will determine whether Ireland’s role in the AI era is seen as an engine of national prosperity or as an enclave of energy-intensive activity that strains the country’s climate ambitions. [1]

##Reference Map:

- [1] (The Irish News) – Paragraph 1, Paragraph 2, Paragraph 3, Paragraph 4, Paragraph 5, Paragraph 7, Paragraph 8

- [2] (The Irish Times) – Paragraph 2, Paragraph 7

- [3] (The Irish Times) – Paragraph 2

- [4] (Mason Hayes & Curran) – Paragraph 4, Paragraph 5

- [5] (CBRE) – Paragraph 6

- [6] (International Energy Agency) – Paragraph 6

- [7] (European Central Bank) – Paragraph 6

Source: Fuse Wire Services